29th October 2019

A hand to mouth existence: the story of Eliza Seymour

Elaine Bradshaw, a member of our poverty project, has been researching the hard lives of some local people in the mid-19th century

We’ve been examining the role of 19th century outdoor relief - publicly-financed poor relief - given in kind and/or in money, to allow poor people to remain in their own homes. Records allow us to follow some of the threads of Eliza Seymour’s sad life

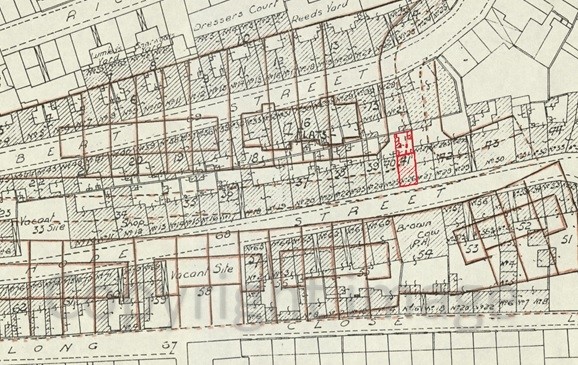

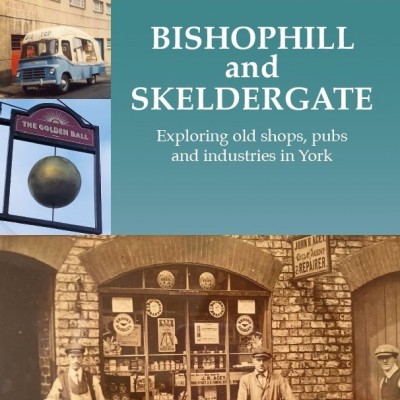

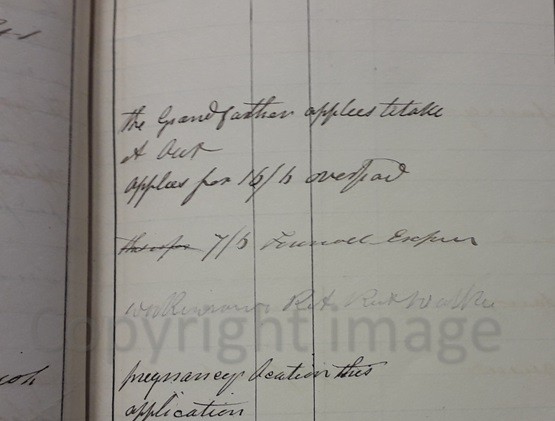

Eliza Seymour was born in 1841, just after her mother, Jane Seymour, died of typhus in the workhouse. As she had been a servant lodging in Nunnery Lane her ‘bastard orphan’ became the responsibility of the parish of St Mary Bishophill Junior. Fortunately there was a willing grandfather, John Seymour, to ‘take it [sic] out’. St Mary Bishophill Junior paid weekly for her keep – 2/6 (2 shillings and 6 pence). Her care probably fell to her uncle George Seymour and his wife Mary, as John was a brickmaker in Dringhouses who worked long hours.

York Poor Law Union : Admissions and Relief Book - PLU3/1/1/10, Q ending Sept 1841, p 20 (© York Explore)

Hope Street was miserably poor, overcrowded and insanitary. However, the household was not destitute. There were two working men earning possibly 18 shillings each per week. Mary Seymour earned another 6 shillings and there was Eliza’s 2/6, and maybe payment for Mary Anne. So they had enough to live on, and a little bit to spare.

Hope Street was miserably poor, overcrowded and insanitary. However, the household was not destitute. There were two working men earning possibly 18 shillings each per week. Mary Seymour earned another 6 shillings and there was Eliza’s 2/6, and maybe payment for Mary Anne. So they had enough to live on, and a little bit to spare.