01st February 2021

Orphans and nurse-children: growing up poor in mid-19th century York

Our research project, Making Ends Meet in Nunnery Lane, has been using Poor Law Records to investigate 19th century poverty locally. A current question is how do we discover the lives of family 'strays' such as orphans? This post from our Poverty Research Group reveals glimpses of their lives – and flags questions that may uncover more about them.

Nurse-children

1861 and 1881 census data for Dale Street, Dove Street and Swann Street reveals seven nurse-children living in the three streets. A nurse-child is defined as 'a child taken into the home of someone who cares for him/her as result of circumstances that require the child's care away from his/her home'. The seven were Margaret Butterfield, Robert D Whate, Henry Jenkins, Walter Henderson, Herbert Ramsdale, James Law and Eliza Annie Milburn. Follow this link to find out what we found out about their lives.

Orphans in the workhouse

Evidence suggests a very fluid and mobile pauper population in mid-19th century England. Studies show that an estimated 29% of the population of York had contact with the workhouse between 1861 and 1881, and this is a similar proportion to that of Brackley in Northants, for example. Individuals had periods of independence, and periods of partial independence supported by families, out-relief and charities (see note 1).

For some orphan children, York Poor Law Union (PLU) assumed responsibility for longer-term care. This was organised in different ways, at different times. Children were accommodated at the workhouse, though separated from adults.

Oliver Twist asking the master of the workhouse for more gruel, standing with his empty bowl and spoon, the shocked mistress of the workhouse behind, a trestle table and benches with poor boys beyond; illustration to Dickens' Oliver Twist. (James Mahoney (1810-1879), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Education of poor children in the community

Local children such as James Law, born in Dale Street in 1860, attended charity schools. He went to the Blue Coat School. Admission was by means of a ballot among subscribers to the school. Parents or guardians had to relinquish control and management of a child during his residence and concede authority to place the child in trade or service. Some 2,048 boys passed through the Blue Coat School, Peasholme Green, between 1705 and 1888, attendance fluctuating between 50 and 70. By the mid-19th century there was a curriculum emphasis on industrial training. Twelve of the boys who left in 1871 went into skilled trades.

There was also Grey Coat School for Girls at 33 Monkgate. The largest number accommodated was 44, between 1872 and 1874. The curriculum here aimed to prepare girls for domestic service.

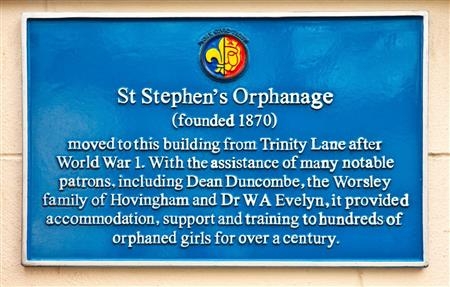

St Stephen's Home was founded as an orphanage in Precentor's Court in 1870. It moved to two houses in Trinity Lane, Micklegate, Bishophill, in 1872, subsequently moving again to 25 and 27 Trinity Lane. After World War 1 it moved to 89 The Mount (now the site of Hotel du Vin).

(York Civic Trust plaque, follow this link for more information)

Apprentices

Charity schools offered three benefits: clothes, a basic education and the necessary premium (or fee) to secure an apprenticeship, an extended period of training in a craft or trade given to a boy by an established master in the trade. This normally lasted until the apprentice was 21, and was the subject of a legal agreement, an indenture. The master provided the apprentice with board and lodging for the period of the apprenticeship. York Poor Law Union also arranged apprenticeships, detailed via this link.

The Poor Law (Apprentices) Act of 1851 improved the lot of workhouse apprentices, making their mistreatment an offence, and requiring regular visits from the union's relieving officer. From the 1840s, an increasing number of unions began providing industrial training within their workhouses. For girls it usually included domestic training to prepare them for service. The children's cottage homes set up from the 1880s also often included industrial training facilities.

Boarding-out

From 1868 boarding-out was considered by the central authority, the Poor Law Board, and its successor body, the Local Government Board (LGB). Boarding-out placed workhouse children in long-term care of foster parents who received a weekly allowance for each child. The system was viewed by Guardians as removing children from the moral contagion of the workhouse. Moreover, it was closest to a 'normal' home life, and economical. However, fear of possible neglect, cruelty or exploitation of boarded-out children made the central authority cautious about sanctioning its use. In 1869 only 21 Unions in England and Wales used boarding-out, covering 347 children, generally with good results.

The Board agreed a wider trial and issued a Boarding-out Order (1870), specifying a Boarding-out Committee be formed in each Union to supervise arrangements. Only orphans and deserted children between two and ten were to be boarded-out, with no more than two in the same home unless brothers and sisters. Foster parents were to sign an undertaking agreeing to 'bring up the child as one of their own children, and provide it with proper food, lodging, and washing, and endeavour to train it in habits of truthfulness, obedience, personal cleanliness, and industry, as well as suitable domestic and outdoor work'. There was a weekly maintenance fee of four shillings maximum.

An 1877 revised Order prohibited boarding-out with foster parents in receipt of poor relief. Further Orders in 1889 provided for boarding-out beyond their own union. By the end of the 19th century around half of unions in England and Wales used boarding-out, with 8,000 orphaned or deserted children placed in homes. Although occasional cases of ill-treatment emerged, these were far outweighed by children's fear of being taken away from their foster homes. The practice was also only suitable for children in long-term care. For the 'ins and outs', scattered homes or cottage homes were more suitable. (Adapted from Peter Higginbotham's website: www.workhouses.org.uk/boardingout)

There are occasional references to Boarded-out children in York PLU documents: for example Ina Dixon (7) and Ann Elizabeth Dixon (6) were boarded-out with William Clarkson (Source: PLU/3/1/1/96, Dec 1882).

As yet we do not know when York began the practice of boarding-out, or how the PLU selected the foster parents and monitored children’s care. Studies elsewhere reveal a range of responses:

-

A study examined the proceedings of an official enquiry into alleged neglect of boarded-out children from Belfast workhouse in 1872, the enquiry taking testimony from the children. The study concluded that community NIMBYism (Not in My Back Yard) was the dominant factor, not systematic neglect or abuse of the children. (note 2).

-

A Swansea study reveals PLB criticism of boarding-out, citing a failure to monitor the quality of care by foster parents (note 3).

Further research

We have glimpsed the lives of orphans and nurse-children. By addressing the following questions we can discover more about how they survived:

-

how significant were kin in fostering?

-

what other assistance existed? For example charitable bodies such as the Blue Coat and Grey Coat Schools, or from York Poor Law Union (PLU)?

-

what contribution did charity schools make to the life chances of orphans?

-

what other charitable support was available, and how was this accessed?

-

in what ways did the PLU assist, such as out-relief, that is domiciliary help in cash or kind? Or assist by workhouse admission, often short-term to deal with a crisis - a temporary shelter for children whose parents could no longer care but who aimed to return later to claim their children.

-

some poor law unions used child migration schemes. Did York PLU use these schemes? If so, to what extent? How did the schemes work? And with what results?

-

what evidence is there of spikes in orphan admissions to the workhouse, prompted by events such as epidemics (e.g. cholera 1848-9)?

-

what other sources might reveal orphan-related experience ? For example autobiographies, directories, newspapers (e.g. 'Respectable family wish to bring up an ORPHAN CHILD born within the year, of healthy Parents and having no Disreputable Connections. Apply with full particulars to the Editor, addressed to “ADOPTION”', Yorkshire Gazette 5 Dec 1857).

We hope this work-in-progress will encourage readers to select a topic to explore. Training in research skills, and support, is available to CHLHG members, if required.

Notes

-

Steven King, 'Thinking and Rethinking the New Poor Law' in Local Population Studies, 99, autumn 2017 p. 14.

-

Olwen Purdue, 'Nineteenth-Century Nimbys, or What the Neighbour Saw? Poverty, Surveillance, and the Boarding-Out of Poor Law Children in Late Nineteenth-Century Belfast' in Family and Community History, 23/2, July 2020, pp. 119-135.

-

Hulonce, Lesley, Pauper Children and Poor Law Childhoods in England and Wales 1834-1910 (Round Globe). https://roundedglobe.com/authors/80c18173-df4e-4787-973d-6a87a8a0cb43/Lesley%20Hulonce/

Thanks to Julie-Ann Vickers, Explore York Libraries and Archives; and to Colin Hinchcliffe and Peter Higginbotham.

Primary sources

Borthwick Institute for Archives, The University of York

YCT/BCS Records of the Blue Coat School, York, 1768-1991

YCT/GCS Records of the Grey Coat School, York, 1789-1961

YCT/SSO Records of St Stephen's Orphanage, York 1875-1975

Census: 1861 and 1881.

Explore York Libraries and Archives PLU/6/1/1 Register of Apprentices. and PLU/1/1/1/1 Board of Guardians Minute Books

Secondary source

Taylor, W.B., Blue Coat: Grey Coat: The Blue and Grey Coat Schools and St Stephen's Home of York (Sessions Book Trust, York, 1997)

Website

www.welcomecollection.org Appendix Vol. XIV. Report to the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress on Poor Law medical relief in certain unions in England and Wales, 1909. By John C. McVail. Credit: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. In copyright

This report reveals organisations supporting York poor include municipal charities, church parishes, income from the Strays, voluntary and endowed charities, thrift agencies (friendly societies and clubs), and trade unions.