Ernest Woodall and the role of decoy ships in World War 1

One of the men commemorated on the Scarcroft Memorial, Ernest Woodall, served on a decoy ship in the First World War. These were a little known response to the threat posed by German U-Boats.

By researching individual human stories it’s possible to learn much more about the historical background to war.

A decoy ship is primarily a ship in disguise and disguise has long played a part in naval warfare. In the great days of sail, paint and false flags were used to get nearer to prize ships and in an attempt to avoid more powerful enemies.

Ernest Woodall was a former pupil of Scarcroft School, whose family lived at 1 Hob Moor Terrace in York. He was born in Ebenezer Place in 1894, in George St in the Walmgate area of York. (There is still a sign for this next to the Phoenix Inn, near the City Walls). Ernest was one of eight children of Albert and Elizabeth Woodall.

Ernest Woodall was a former pupil of Scarcroft School, whose family lived at 1 Hob Moor Terrace in York. He was born in Ebenezer Place in 1894, in George St in the Walmgate area of York. (There is still a sign for this next to the Phoenix Inn, near the City Walls). Ernest was one of eight children of Albert and Elizabeth Woodall.

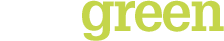

Ernest’s death by drowning during World War is commemorated on the Scarcroft School Memorial and also on the memorial at Dringhouses and the Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

Ernest’s death by drowning during World War is commemorated on the Scarcroft School Memorial and also on the memorial at Dringhouses and the Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

He had been working as a carriage painter at the railway wagon works in York, before signing up for 12 years to the Royal Navy, in August 1912, as soon as he was 18. This was of course before the war started. His service record describes Ernest as having brown hair and blue eyes, with a fresh complexion.

He had been working as a carriage painter at the railway wagon works in York, before signing up for 12 years to the Royal Navy, in August 1912, as soon as he was 18. This was of course before the war started. His service record describes Ernest as having brown hair and blue eyes, with a fresh complexion.

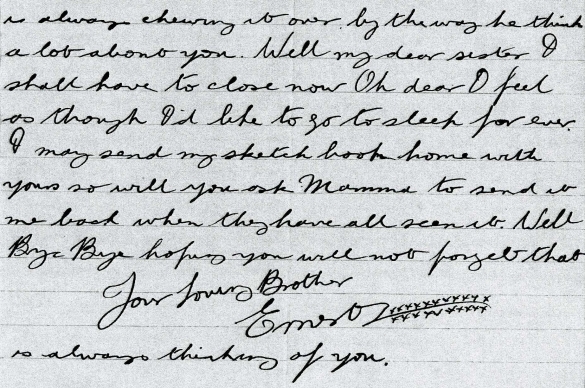

He served on a number of ships as a painter. In a letter to his sister Doris in 1915, Ernest wrote about the thousands of tons of coal they took in at different times and ‘the worst of it is we never see a fire from year end to year end except in the galley, that is where they cook our grub.’ He ends ‘Oh dear I feel as though I’d like to go to sleep for ever. I may send my sketch book home with yours so will you ask Mamma to send it me back when they have all seen it’.

He served on a number of ships as a painter. In a letter to his sister Doris in 1915, Ernest wrote about the thousands of tons of coal they took in at different times and ‘the worst of it is we never see a fire from year end to year end except in the galley, that is where they cook our grub.’ He ends ‘Oh dear I feel as though I’d like to go to sleep for ever. I may send my sketch book home with yours so will you ask Mamma to send it me back when they have all seen it’.

He joined HMS Cullist on 12 May 1917, and in August of that year he married Maud Marion Beckingham, a young widow, in Portsmouth.

He joined HMS Cullist on 12 May 1917, and in August of that year he married Maud Marion Beckingham, a young widow, in Portsmouth.

HMS Cullist was a cargo steamship, formerly known as Westphalia and Jurassic, which served as a decoy Q-ship. This was a very dangerous ship on which to serve, and sadly it was torpedoed by U-boat U-97 and sunk within two minutes in the Irish Sea, off Drogheda at Dunanet Point, on 11 February 1918. Ernest was one of the 43 men who drowned as a result.

Cliff McMullen wrote about Q ships in 2001: “Submarine decoy vessels were developed because of the large loss of shipping caused by German U-boats in the opening months of the war. It did not go unnoticed that the submarines preferred to attack unescorted, older and smaller vessels, by using surface gunfire, thus preserving their torpedoes for larger vessels or warships and extending their sea cruise durations. Thus it was conceived that a vessel, such as a coaster, if provided with a concealed armament, could meet a surfaced submarine on fairly equal terms. The vessels chosen, code-named Q-ships by the Admiralty and also known as Decoy Vessels and Special Service Ships, were comparatively small, ranging in size from 4,000 tons to small sailing ships, old and made to look poorly maintained. Their outward appearances were indistinguishable from ordinary merchantmen. When attacked, the Q-ship would allow the U-boat to come as close as possible before dropping the disguise, raising the White Ensign (a requirement of international law ), and opening fire. The sinking of about 30% of the U-boats destroyed by surface forces by this method proved its success. In the early part of the war when successes were highest, the number of such vessels was limited but, later as the numbers increased, the Germans became aware of the operation and successes declined. One source has been quoted that there were as many as 366 Q-ships, of which 61 were lost during the war, nearly all the larger vessels being torpedoed without warning.

The Q-ships armament, usually consisting of one 4-inch (102 mm) and two 12-pdr guns, was disguised in various ways: behind hinged bulwarks, inside dummy superstructures and deck cargoes, and even inside dummy boats. The ships adopted greater secrecy and elaborate disguises. They changed their disguises and names from time to time, some vessels having had as many as five different names. Many ruses were developed to convince the U-boats that vessels were genuine. These included disguises for the crew - men made up as black merchant seamen, the captain's 'wife', and in one crew the 'cook' was equipped with a stuffed parrot in a cage. Also a simulated abandon-ship routine was operated whereby half the crew, nicknamed the 'panic party', would leave ship while the other half would remain hidden aboard to man the guns. When it became apparent that the decoys were likely to be torpedoed, their holds were filled with buoyant material to keep them afloat.” (see http://www.gwpda.org/naval/rnqships.htm)

Serving as a painter,1st class in the Royal Navy, Ernest was awarded a 1915 Star, a Victory Medal and a British War Medal. The ship’s commander, Lieutenant Commander H. Simpson, was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and Bar and also the Croix de Guerre in 1918, for his role in the action with enemy submarines.

Serving as a painter,1st class in the Royal Navy, Ernest was awarded a 1915 Star, a Victory Medal and a British War Medal. The ship’s commander, Lieutenant Commander H. Simpson, was awarded a Distinguished Service Order and Bar and also the Croix de Guerre in 1918, for his role in the action with enemy submarines.

You can read more about Q-ships in E Keble Chatterton: Q-Ships and their Story, which was published in 1922. It's available to read online here

Many thanks to the Woodall family - John, Stephen and Patricia for proving material about Ernest.