View navigation

Surname |

Wifefirst name |

Husbandfirst name |

Colony where husband is |

Date of conviction |

Number and gender of children |

Fowler |

Ann |

Henry |

Norfolk Island |

01/07/34 |

2M 1F |

Hudson |

Elizabeth |

William |

NSW |

01/01/38 |

3M 3F |

Hughes |

Frances |

Thomas |

VDL |

18/10/41 |

1M 2F |

Hare |

Ann |

George |

VDL |

01/10/42 |

2M 1F |

Reed |

Elizabeth |

John |

VDL |

01/06/38 |

3M 2F |

In 1841 Elizabeth (47) was living in Malt Shovel Yard, Walmgate in St Dennis parish with William (12), Priscilla (9), Joseph (7) and John (3). Neighbours have skilled occupations – e.g. blacksmith, cabinet maker, and hairdresser – perhaps hinting that the family did not occupy the most basic housing. The 1851 census records Elizabeth, a charwoman, now living nearby in St Dennis Street. Joseph is a glass blower's apprentice and John a labourer at the glassworks. William Hall - a journeyman joiner (55) – lodges with them, supplementing the household income.

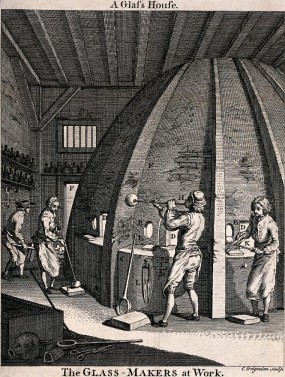

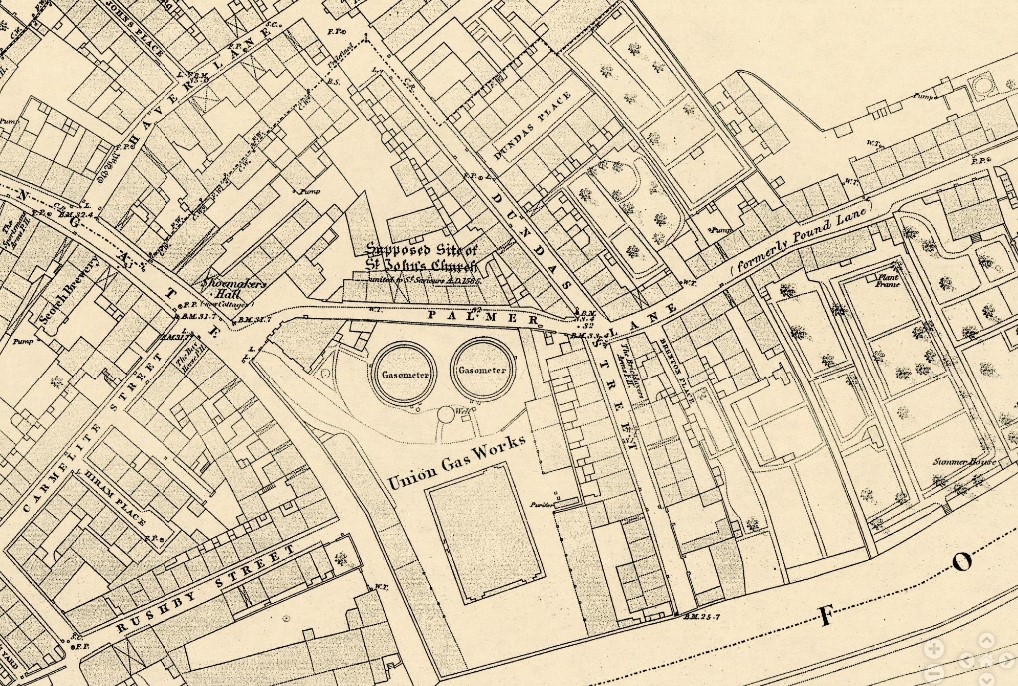

In 1841 Elizabeth (47) was living in Malt Shovel Yard, Walmgate in St Dennis parish with William (12), Priscilla (9), Joseph (7) and John (3). Neighbours have skilled occupations – e.g. blacksmith, cabinet maker, and hairdresser – perhaps hinting that the family did not occupy the most basic housing. The 1851 census records Elizabeth, a charwoman, now living nearby in St Dennis Street. Joseph is a glass blower's apprentice and John a labourer at the glassworks. William Hall - a journeyman joiner (55) – lodges with them, supplementing the household income. Joseph progressed from apprentice to glass blower, then bottle maker by 1901, living in Hope Street, Walmgate, with his wife Jane. They do not have any children and may have been in a position to contribute to the wider family income. John progressed from glassworks labourer in 1851 to glass blower in 1861, remaining in that job until at least 1901. He married and had a family.

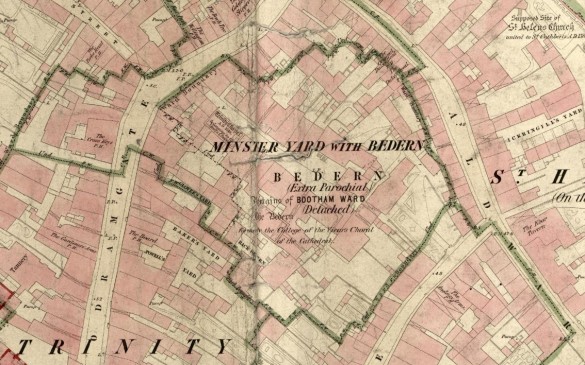

Joseph progressed from apprentice to glass blower, then bottle maker by 1901, living in Hope Street, Walmgate, with his wife Jane. They do not have any children and may have been in a position to contribute to the wider family income. John progressed from glassworks labourer in 1851 to glass blower in 1861, remaining in that job until at least 1901. He married and had a family. Frances Hughes was born in 1814, St Mary Bishophill Senior her parish of settlement. In 1841 she is in the workhouse with her three children William (9), John (5) and Frances (1). In June 1841, three months after admission, she is sentenced to fourteen days imprisonment in the House of Correction in Bishophill. Her daughter goes with her.

Frances Hughes was born in 1814, St Mary Bishophill Senior her parish of settlement. In 1841 she is in the workhouse with her three children William (9), John (5) and Frances (1). In June 1841, three months after admission, she is sentenced to fourteen days imprisonment in the House of Correction in Bishophill. Her daughter goes with her.

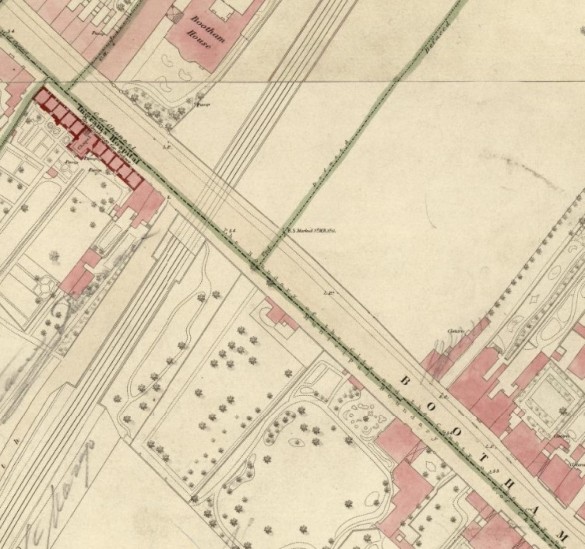

In 1851 Elizabeth was in Wilson's Passage, Gillygate, generating income as a charwoman. Charles (20) was a confectioner's apprentice, Reuben (16), a tailor's apprentice and Mary Ann, a scholar. Ten years later Elizabeth is an upholstress, a widow living alone at 42 Bootham. By 1871 she had moved nearby to Ingram's Hospital, Bootham, an almshouse for ten poor widows, built between 1630 and 1640. In 1881 she is there (her address 71 Bootham), with her grandson John James Reed (24, a tailor) and Elizabeth (10).

In 1851 Elizabeth was in Wilson's Passage, Gillygate, generating income as a charwoman. Charles (20) was a confectioner's apprentice, Reuben (16), a tailor's apprentice and Mary Ann, a scholar. Ten years later Elizabeth is an upholstress, a widow living alone at 42 Bootham. By 1871 she had moved nearby to Ingram's Hospital, Bootham, an almshouse for ten poor widows, built between 1630 and 1640. In 1881 she is there (her address 71 Bootham), with her grandson John James Reed (24, a tailor) and Elizabeth (10).