26th June 2022

The story of the scoria brick: a recycling success

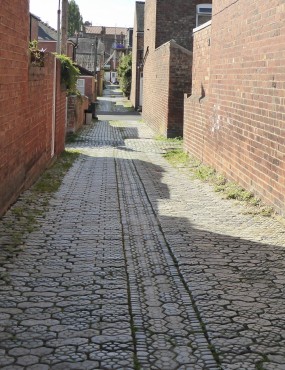

Have you ever wondered why we have all those silvery blue tiles in our back alleyways and gutters? Not just in South Bank and Clementhorpe, with long stretches behind our terraced houses, but in many other parts of York, such as Burton Stone Lane, Haxby Road, Heworth, Fulford, Leeman Road, Acomb, and the Groves.

Have you ever wondered why we have all those silvery blue tiles in our back alleyways and gutters? Not just in South Bank and Clementhorpe, with long stretches behind our terraced houses, but in many other parts of York, such as Burton Stone Lane, Haxby Road, Heworth, Fulford, Leeman Road, Acomb, and the Groves.

People have fond childhood memories of playing out on them with marbles and learning to ride bicycles, but they were apparently less successful for roller skating, and they could be a bit slippery in icy weather.

These elaborate double hexagon-shaped tiles were called various names, such as ‘threepenny bits’, ‘eights’, or ‘figures of eight’. In our area a particularly distinctive back alley runs between Lorne St and the bottom of Count de Burgh Terrace, where in this case the bricks are square, but very blue, almost like a Turkish bath.

At our recent Bishy Road Street Party display, a conversation with Peter Gidley about similar distinctive paviors in his home town of Darlington led us to find out about their origin. They are actually called scoria bricks. Interestingly the word scoria is an ancient Greek word, meaning excrement or dung, and the Romans apparently used this word for hot lava bursting out of a volcano.

At our recent Bishy Road Street Party display, a conversation with Peter Gidley about similar distinctive paviors in his home town of Darlington led us to find out about their origin. They are actually called scoria bricks. Interestingly the word scoria is an ancient Greek word, meaning excrement or dung, and the Romans apparently used this word for hot lava bursting out of a volcano.

The story of these bricks starts in the mid-19th century, when Teesside industrialists had a problem with removing molten waste from the bottom of a blast furnace, known rather more prosaically as slag. Millions of tons of pig iron were being produced in Cleveland in the North East of England at the time, generating much slag waste, a real problem for the ironmasters, as it was expensive to remove. One option was to make slag wool, used for insulation. ‘Basic slag’ was also used as a fertiliser on fields, even in the 1950s, as it contained lime and released phosphates when buried.

The story of these bricks starts in the mid-19th century, when Teesside industrialists had a problem with removing molten waste from the bottom of a blast furnace, known rather more prosaically as slag. Millions of tons of pig iron were being produced in Cleveland in the North East of England at the time, generating much slag waste, a real problem for the ironmasters, as it was expensive to remove. One option was to make slag wool, used for insulation. ‘Basic slag’ was also used as a fertiliser on fields, even in the 1950s, as it contained lime and released phosphates when buried.

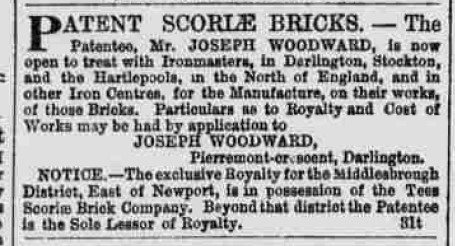

But a smart Victorian idea was to make shiny silvery-blue bricks as a road or alleyway surface, a really good recycling solution. Joseph Woodward, a Darlington man, had taken a patent out in 1869 on a device to deal with the waste efficiently, and his Tees Scoriae Brick Company opened at Clay Lane Blast Furnace in Eston, Middlesbrough in 1872 for this purpose.

But a smart Victorian idea was to make shiny silvery-blue bricks as a road or alleyway surface, a really good recycling solution. Joseph Woodward, a Darlington man, had taken a patent out in 1869 on a device to deal with the waste efficiently, and his Tees Scoriae Brick Company opened at Clay Lane Blast Furnace in Eston, Middlesbrough in 1872 for this purpose.

Northern Echo, 1 November 1873

By 1873 he was advertising for ironmasters to allow him to make his bricks at their works, and exhibited at a stand at the Yorkshire Show in 1878 at Northallerton, where he paved an area suitable for stables. In 1875 he was at the Ripon Agricultural Show, proudly announcing that Darlington Corporation had trialled his bricks successfully for two years in one of their main streets. By now Woodward was living in Bedale, at Carthorpe House.

His process involved molten slag being tapped from the bottom of the blast furnaces and transported in bogies down a railway to his patent revolving table, to be tipped into brick-shaped moulds and cooled. After two minutes, the slag was still red hot, but set, then at the vital moment, the turning motion of the table tipped the brick out of the mould and onto a conveyor belt which carried it into an oven, heated by the furnace. Bricks were then cooked in this annealing kiln for three days, until ready to use. The company opened factories at Acklam in Middlesborough and Lackenby at Redcar, next to blast furnaces. They also expanded to a location at the Cargo Fleet Iron Works, and when the Institution of Mechanical Engineers visited in 1893 they described the wheel, fitted with 140 moulds, and 18 kilns, each holding 1000 bricks.

Scoria bricks were a kind of basalt, an igneous rock, very hard to break, very durable, completely waterproof, frost-proof and indeed chemical-proof, proving very useful in drainage channels at ICI Billingham in the 1920s. Scoria bricks were identical in size, thus easily laid flat on roads, on a 6in bed of sand, to be compressed down by men with heavy wooden rammers. They were also known as stable bricks, due to their ideal use for horse stable flooring. They did have some memorable characteristics, apparently they were liable to explode shockingly if heated around a fire, and they smelt of sulphur/rotten eggs if split. People also remember their echoey ring as a surface.

In 1875 Joseph Woodward wrote an angry letter to the York Herald, outraged that his scoria bricks had been dismissed as a ‘failure’ in the paper by a New York critic, Luckenbach, a competitor, despite their successful use over the north of England.

Scoria bricks were used in the approaches to the new railway station at York, which opened in 1877, and also at Edinburgh. Huge quantities of scoria bricks were manufactured on Teesside, with many exported to Canada and the West Indies, as well as Holland, Belgium, the US, South America and Africa.

There were several patterns, to be found all over the North East back alleys. Our distinctive double hexagon shape was designed to lock together with its neighbour. It is not clear when our alleyways were paved, but in 1884 York Council’s Urban Sanitary Committee accepted a tender from the company for the supply of slag bricks at £8 2s 6d per 1000.

Eventually however the motor car destroyed the business, when it replaced metal-rimmed carriages, as people wanted a smoother ride, and tarmac started to follow in the 1930s. Steel and iron making ran down and by 1966 the Company went bankrupt, to be wound up in 1972.

In 2004 the City of York Council produced a report about their resurfacing policy on back lanes, referring to the bricks rather mysteriously as Rosemary setts. Apparently York has around 16 miles (25 km) of back lanes, a third of which use scoria bricks. These were tougher in withstanding bin lorries and freezing temperatures than paving or tarmac. But sadly alleys have been excavated for utilities and street lighting, and in many cases the scoria bricks have been patched with tarmac, as they are no longer available for replacement.

These bricks can be found at Beamish Open Air Museum, and the paving has inspired art works too. The first floor extension of York Art Gallery included more than 300 double hexagon shaped tiles fitted to the exterior of the Centre of Ceramic Art (CoCA) in 2015. In 2021 Bristol sculptor Jo Lathwood featured the bricks in ‘Volcanoes and Scoria Bricks’, a performance at the Darlington Head of Steam Museum.

Sources

Many thanks to Peter Gidley for setting us off on this story. There is also much material in the York Past and Present Facebook group, posted by John Grant in 2015. For more details see:

-

Northern Echo, 1 November 1873

-

Richmond & Ripon Chronicle, 24 July 1875

-

Birmingham Daily Post, 29 December 1876

-

York Herald, 20 July 1877

-

Northern Echo, 14 July 2008

-

http://yorkstories.co.uk/paving-part-2-down-the-alleys (thanks to Lisa for drawing our attention to the Council report)

-

http://www.hidden-teesside.co.uk/2019/10/12/tees-scoria-brick-company-wharton-arms-skelton/

-

https://northeastbylines.co.uk/scoria-bricks-history-at-our-feet/

-

https://www.darlingtonandstocktontimes.co.uk/news/20001616.almost-unbreakable-slag-bricks-lined-streets-tees-valley/

-

https://madliam.blogspot.com/2021/05/rosemary-and-honey-on-back-streets-of.html