York waifs and strays: Ina and Nancy Dixon are boarded out

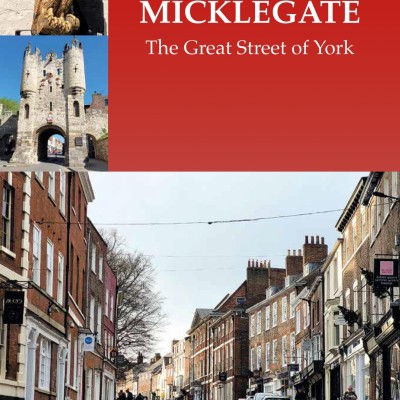

In 1881 York Poor Law Union set up a pilot scheme to test the feasibility of boarding out (fostering) abandoned or orphaned children in its care (see York waifs and strays) Ina and Nancy Dixon, deserted by their parents, were among the twenty children selected. They were boarded with William and Selina Clarkson, who had never had any children of their own and the experiment proved very successful. They had a stable childhood and education, attending Micklegate School, and remained close to the Clarksons after they grew up and had families of their own. This is their story.

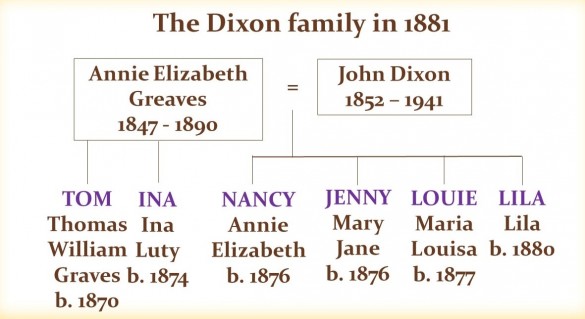

Four little girls, Ina, Jenny, Nancy and Louie Dixon, all under six years old, ended up in the York Union Workhouse after being deserted by their parents.

In a perfect world, their father John Dixon would have become a small farmer like his father James, who owned land and property in Huntington. But the 1870s brought a severe agricultural depression, John’s father sold up and John had to become an agricultural labourer, with a small wage and a large family to support.

Just before his youngest daughter Lila was born, he hit rock bottom and had to ask the Poor Law Union for help. Although destitute, he was able-bodied and in work, so he received only a very grudging hand-out of provisions. John’s wife Annie may also have been struggling, as Lila was her fifth child in six years, and at some point in 1880 the older girls moved to Osbaldwick, which suggests they were with their maternal grandmother Mary Pearson. On 26 November, they were admitted to the Workhouse from Osbaldwick. Unfortunately, the Application and Report Books for this period are missing, so the exact circumstances are a mystery, though later documents confirm that the Poor Law Union had no idea who the children’s parents were. The Workhouse Admissions book provides a very basic reason for their admittance: “Sick”.

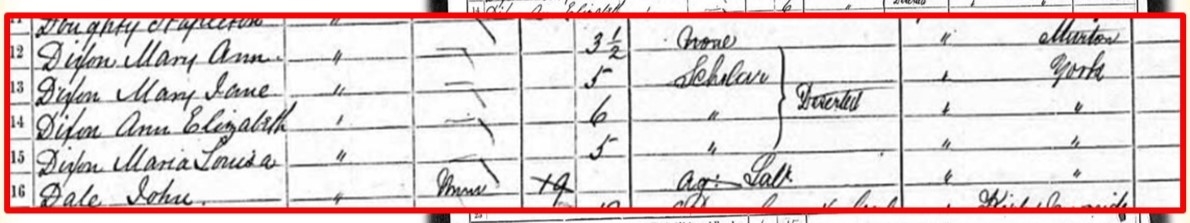

The four sisters were in the Workhouse when the 1881 Census was taken but, although they had been there for around four months, the staff were unclear about which one was which. In mitigation, Census Day required the staff to fill in details of over 700 people, put them into rough alphabetical order and arrange them in family groups, so it is not surprising that errors were made.